(This is a write-up of a talk I gave to the Ann Arbor R User Group, earlier this month.)

It seems like the longer one works with data, the probability they are tasked to work with unstructured text approaches 1. No matter the setting –whether you’re working with survey responses, administrative data, whatever– one of the most common ways that humans record information is by writing things down. Something great about text-based data is that it’s often plentiful, and might have the advantage of being really descriptive of something you’re trying to study. However, the path to summarizing this information can feel daunting, especially if you’re encountering it for the first time.

With this perspective in mind, I want to write down some basics regarding the excellent R package, tidytext, which follows principles of the tidyverse in encouraging the use of tidy data (c.f. Wickham, 2014). Julia Silge and David Robinson (the authors of tidytext) have also written a book on using the package in combination with other tools in the R language to analyze text. The full-text is free online, and you can also purchase a paper copy through O’Reilly. If you find this post useful, I would recommend moving onto their book as a more thorough guide, with many useful examples.

what we’ll do in this post

I’m aiming for 3 things:

- Basic vocabulary around text analysis, as related to tidytext functions

- Demonstrate tokenization and pre-processing of text

- Describe some textual data

For this exercise, I’ve pulled down the transcript of the October democratic party primary debate from 10/15/2019. I wanted to work with something fresh, and for this post we can imagine ourselves as a data journalist looking to describe patterns of speech from the different candidates.

fundamental units of text: tokens

Our first piece of vocabulary: “token”. A token is a meaningful sequence of characters, such as a word, phrase, or sentence. One of the main tasks of mining text-data is converting strings of characters into the types of tokens needed for analysis; this process is called tokenization. As far as how this is accomplished with tidytext, the workflow is to create a table (data.frame/tibble) with a single token per row. We accomplish this step using the unnest_tokens() function.

library(tidyverse)

library(tidytext)

library(scico)

# load the debate transcript data

wp <- read_rds("../../static/post/20191017-tidytext-overview/data/20191110-oct-dem-debate-cleaned.rds")

# Cooper's introduction to the debate

wp[[2, 3]] %>% str_sub(1, 128)## [1] "And live from Otterbein University, just north of Columbus, Ohio, this is the CNN-New York Times Democratic presidential debate."dd_uni <- unnest_tokens(

tbl = wp,

output = word,

input = txt,

token = "words", # (default) tokenize strings to words

to_lower = TRUE, # (default) set the resulting column to lowercase

strip_punct = TRUE # (default) scrub the punctuation from each word

)

# the same line, tokenized into single words (unigrams)

filter(dd_uni, index == 1)## # A tibble: 112 x 3

## speaker index word

## <chr> <int> <chr>

## 1 Cooper 1 and

## 2 Cooper 1 live

## 3 Cooper 1 from

## 4 Cooper 1 otterbein

## 5 Cooper 1 university

## 6 Cooper 1 just

## 7 Cooper 1 north

## 8 Cooper 1 of

## 9 Cooper 1 columbus

## 10 Cooper 1 ohio

## # … with 102 more rowsSo, from an initial data frame, we’ve gone from a single row per string to rows for each resulting token. The unnest_tokens() function is key to much of what you’ll do with tidytext, so getting familiar with it is important. Now, because each word is now a row of text, we can start to use existing functions from to do some basic analysis. What if we wanted to track the mentions of terms related to a given topic, like healthcare? Here we’ll create a vector of words, and use cumsum() to track running totals within each speaker.

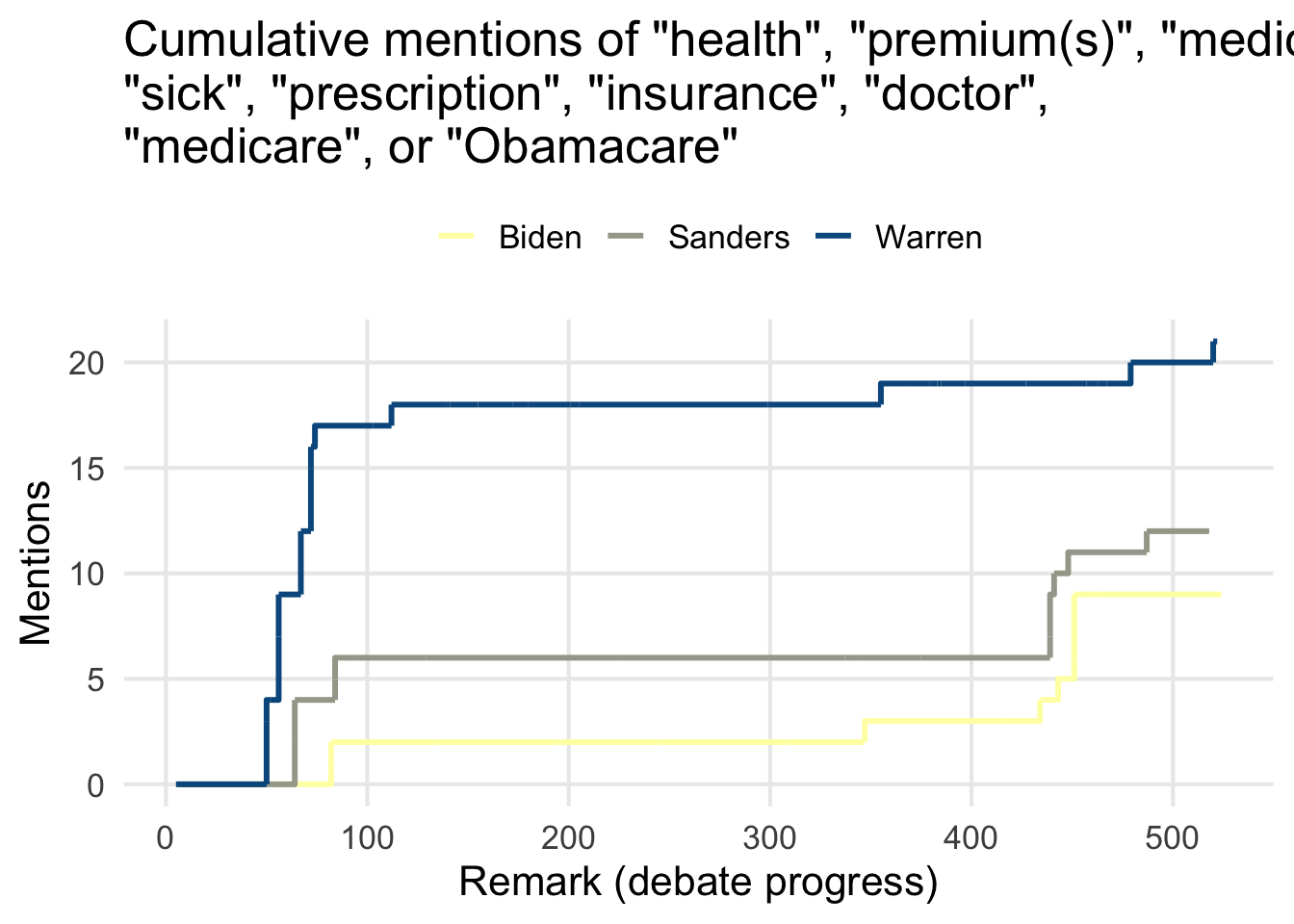

hc_terms <- c(

"health", "premium", "premiums",

"medicare", "sick", "prescription",

"insurance", "doctor", "medicare", "obamacare"

)

# looking at the top 3 candidates

dd_uni %>%

filter(speaker %in% c("Biden", "Warren", "Sanders")) %>%

group_by(speaker) %>%

mutate(hc = cumsum(word %in% hc_terms)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = index, y = hc, color = speaker)) +

geom_step(size = 1.05) +

scale_color_scico_d(name = "", palette = "nuuk", direction = -1) +

labs(

x = "Remark (debate progress)",

y = "Mentions",

title = 'Cumulative mentions of "health", "premium(s)", "medicare",\n"sick", "prescription", "insurance", "doctor",\n"medicare", or "Obamacare"'

)

Here you can see Sanders and Warren responding to questions about their policies/plans during the beginning of the debate, and when Sanders and Biden revisit the topic of the insurance industry near the end.

But, you’re definitely not restricted to using just single words! Maybe we want to look for important phrases important to the debate, like “Medicare For All”. A phrase like “Medicare For All” can be thought of as what’s called an n-gram, specifically a trigram. N-grams are just a sequence of n items from a sample of text or speech; in our case our unit/item is words.

We can use unnest_tokens() to pull out all the different trigrams found in our text, and (because the function returns a tidy data frame!) we can then use dplyr::count() to see how many times a given trigram is mentioned.

dd_tri <- unnest_tokens(wp, trigram, txt, token = "ngrams", n = 3)

# count the prevalence of all trigrams found

count(dd_tri, trigram, sort = TRUE) %>%

slice(1:15)## # A tibble: 15 x 2

## trigram n

## <chr> <int>

## 1 thank you senator 59

## 2 <NA> 43

## 3 we have to 42

## 4 the united states 37

## 5 we need to 35

## 6 in this country 33

## 7 i want to 31

## 8 we're going to 31

## 9 make sure that 26

## 10 the american people 26

## 11 on this stage 25

## 12 one of the 21

## 13 are going to 19

## 14 medicare for all 18

## 15 thank you mr 18From this little exercise, it looks like a transitional phrase, “Thank you Senator” (used mostly by the moderators), is the most frequent trigram. However, something worth noting is that the next most common instance is NA– what’s going on here? These simply represent comments that had fewer than 3 words. This is something that we’ll see given that we’re looking at transcribed speech (as opposed to written responses), so it’s important to think about idiosyncracies you might encounter depending on the data you’re analyzing.

handling non-informative words or tokens

In many analyses, it might be important to discard words that aren’t useful or helpful to descrbing the data you’re working with. In natural language processing, these terms/words are referred to as stop words, and they’re generally the most common words found in a language. In the English language, some common stop words include “I”, “is”, “of”, “are”, and “the”. There isn’t a universally accepted list of words that should be discarded, and it’s frequently necessary to augment an existing list with entries that are specific to a given project. For example, we could think about removing the word “senator”, given that many of the debate participants are senators and its usage would be similar to how an honorific like “Mr.” or “Mrs./Ms.” might be used throughout the debate. The tidytext package helpfully includes several lists of stop words, which are a useful starting place for this task. The helper function get_stopwords() enables you to select from a set of 3 lexicons, and supports Spanish, German, and French (in addition to English).

smart_stops <- get_stopwords(language = "en", source = "smart")

head(smart_stops)## # A tibble: 6 x 2

## word lexicon

## <chr> <chr>

## 1 a smart

## 2 a's smart

## 3 able smart

## 4 about smart

## 5 above smart

## 6 according smart# here's Cooper's introduction again

# this time we'll drop unigrams that match terms from our list of stop words

dd_uni %>%

anti_join(smart_stops, by = "word") %>%

filter(index == 1)## # A tibble: 65 x 3

## speaker index word

## <chr> <int> <chr>

## 1 Cooper 1 live

## 2 Cooper 1 otterbein

## 3 Cooper 1 university

## 4 Cooper 1 north

## 5 Cooper 1 columbus

## 6 Cooper 1 ohio

## 7 Cooper 1 cnn

## 8 Cooper 1 york

## 9 Cooper 1 times

## 10 Cooper 1 democratic

## # … with 55 more rowsNote that because each unigram is stored as a row in the data frame, and each stop word is stored as a row in its own data frame, we’re able to discard the ones we don’t want by using dplyr::anti_join().

pulling everything together: using term frequencies and document frequencies

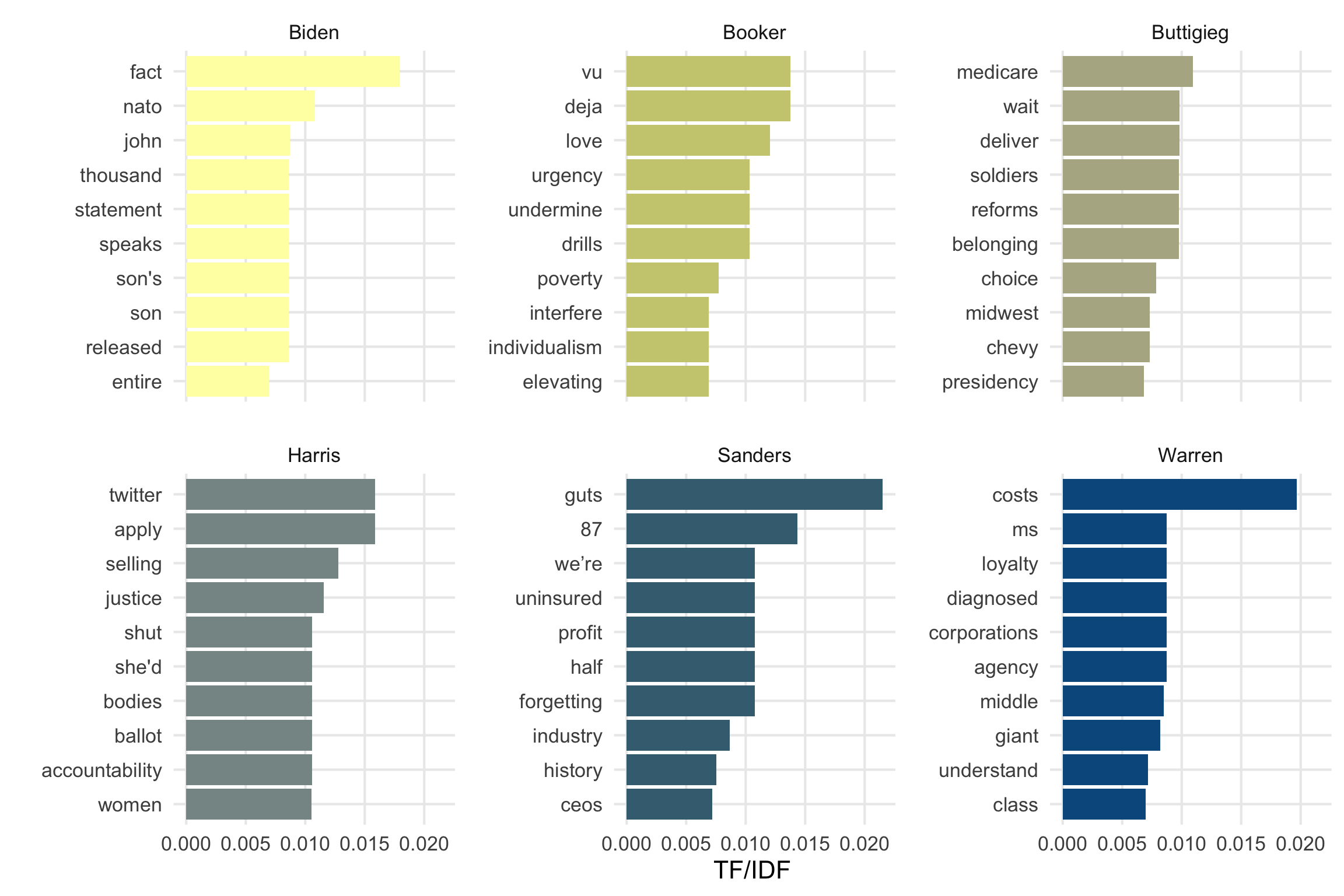

Next we’ll pull each of these preceding steps together to try and identify distinctive words from some of the leading candidates. One common approach to doing this is by generating TF/IDF scores of given terms. TF/IDF is a combination of term frequency and (inverse) document frequency.

Term frequency is merely the fraction of times that a term (in this case, word) appears in a given document.

\(tf(t,d) = \frac{f_{t,d}}{\sum\limits_{t'\in d} f_{t',d}}\)

Document frequency is the number of times a term appears across all documents in a collection. In this case, the measure is inverted so that terms that appear in a small number of documents receive a larger value.

\(idf(t,D) = log\frac{N}{1 + |d \in D : t \in d|}\)

Lastly, the two measures are combined as a product; terms that are found frequently in a small number of documents get higher scores, whereas terms that are found in virtually every document receive lower scores.

\(tfidf(t,d,D) = tf(t, d) \cdot idf(t, D)\)

Calculating each of these metrics is straightforward using the bind_tf_idf() function. bind_tf_idf() simply needs a document ID, a term label, and a count for each term; the results are added to the source data.frame/tibble as new columns. In this case we’ll be treating all the text from each speaker in the debate as a document (thus IDF will be high if every speaker uses a given term).

# create unigrams, drop stop words, calculate metrics

# then, keep each speaker's top 10 terms

top_10_tfidf <- wp %>%

unnest_tokens(word, txt) %>%

anti_join(smart_stops, by = "word") %>%

count(speaker, word) %>%

bind_tf_idf(word, speaker, n) %>%

arrange(speaker, desc(tf_idf)) %>%

group_by(speaker) %>%

slice(1:10) %>%

ungroup()Next, because we’re still working with a tibble, it’s simple to visualize these terms and metrics. We’ll be using ggplot2 as before, but there are a few extensions in tidytext worth mentioning, specifically reorder_within(). Facets are a super useful aspect of ggplot’s repertoire, but I’ve occasionally found myself struggling to neatly organize factors/categories across panels. I’ve especially encountered this when working with text and unique tokens that aren’t common across different documents. reorder_within() handles this within aes(), simply taking the vector to be reordered, the metric by which the vector should be sorted, and the group/category that will be used for faceting. The only other thing needed is to add scale_x/y_reordered() as an additional layer, and to make sure that the scales for the reordered axis are set as “free” within facet_wrap() (or facet_grid()).

top_10_tfidf %>%

filter(speaker %in% c("Biden", "Warren", "Sanders", "Buttigieg", "Booker", "Harris")) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = reorder_within(word, tf_idf, speaker), y = tf_idf, fill = speaker)) +

geom_col() +

scale_fill_scico_d(palette = "nuuk", direction = -1) +

scale_x_reordered() +

facet_wrap(~speaker, scales = "free_y", nrow = 2) +

labs(x = "", y = "TF/IDF") +

theme(

legend.position = "none",

panel.spacing = unit(1.5, "lines")

) +

coord_flip()

wrap-up

Okay, I think that was a fairly quick overview of some of tidytext’s capabilities, but there’s so much more beyond what I’ve covered here! I really recommend looking at Julia & Dave’s book, and I’d like to explore some other analysis methods (such as topic modeling, which tidytext supports) in future posts. Please feel free to let me know if you’ve found this useful, or if there’s something I can better explain. Happy text mining!